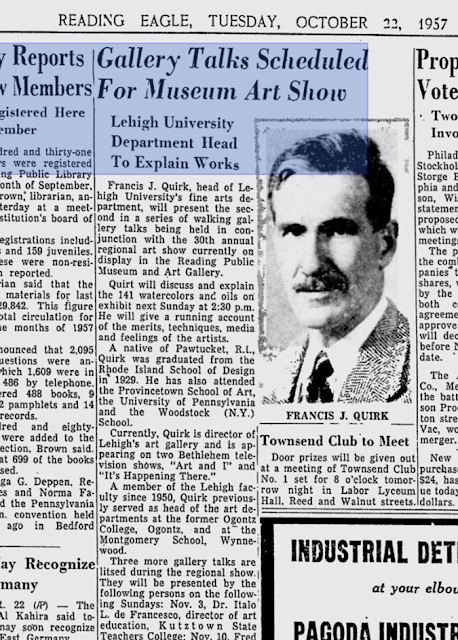

In searching for paintings by Francis Quirk, we came across this sad story about vandalism at Allentown Pennsylvania's Dieruff High School. In the senseless attack on the School's Art Museum one of Quirk's paintings, a portrait appears to have been extensively damaged. The decision was made not to repair it.

A New Life For Ruined Works At Dieruff High's Museum Of Art

|

| Allentown's DieRuff High School's Art Museum once housed a Quirk Portrait in its Art Museum |

Peter Sardo felt honored. It was Dieruff High School's

1988 commencement, and his retirement as head of social studies was

celebrated by the informal rededication of the permanent art collection,

which he helped establish in 1965 and had more or less shepherded ever

since.

Principal Michael P. Meilinger personalized the announcement by picking up Sardo, who had taught Meilinger everything from shared management of schools to rock formations to good living in New York City.

Two weeks later Sardo felt sick. The June morning began promisingly, with Sardo returning to

Dieruff to discuss his dedicatory plaque with Meilinger. The day went downhill when they learned that less than eight hours earlier an alumnus, thinking he was the skipper of "Star Trek," had ruined 17 of the 70 artworks.

Sardo cried and cursed at canvases yanked from frames, paintings dented by feet, watercolors ripped like confetti. To make matters worse, a school employee had tossed pieces of the collection into a dumpster.

"I seldom swear, except `damn' or `hell,' but I'm sure I said a few choice words that couldn't be taped," claims Sardo, who for three decades taught geography and geology at Dieruff and Muhlenberg College. " ... It was the antonym of exhilaration: it was debilitation." He remembers only one event more terrible, and that was the death of an 18-year-old son from a brain tumor.

Sardo feels better these days. After a year-plus restoration, and three lengthy postponements, the Dieruff collection was finally, officially, named for him on May 7. Now when he visits the school, he feels more like himself, more like the teacher who would see an artwork in the lobby, or the library, or the sculpture garden, and be challenged "to do my best to advance the cause of education."

Determining the price of mutilation caused the first delay, says Dennis Danko, caretaker of the Dieruff collection since 1986. According to the head of the school's art and music departments, appraisal to reimbursement took about a year.

Prior to damage the 17 pieces were valued at $15,100, notes Ron Engleman, business manager for the Allentown School District (Danko's guesstimate for the whole collection is $100,000). Damaged, the 17 pieces were worth $1,025. To restore the artworks, plus such items as a freedom shrine and photos of Dieruff principals, cost $9,492. Insurance paid for everything but the $1,000 deductible. The remainder came from the school district's general fund.

Delay No.2 involved restoring the restorer. James Brewer III, a conservator from Revere, Bucks County, worked for about two months, then underwent his second and third heart-bypass operations. He recuperated for approximately a year.

Brewer had many opportunities to act like a surgeon during his year and a half on the Dieruff items. Some were slashed. Others were deeply dented. Many carried the vandal's blood. The assignment was nothing new for Brewer, who has sealed the "X" of an ex-wife's razor blade, rubbed off linseed oil applied lovingly but wrongly every five years, and removed everything but an artist's blood.

Ask Brewer for a sample of his Dieruff work, and most likely he will mention Clarence Carter's "Study for Over and Above, #19." Artist and restorer have been partners for 15 to 20 years. One time, Brewer refurbished a Carter painting that had spent decades in a woodshed. This time, he had to bind six pieces of gouache on cardboard without damaging the watercolor.

Brewer began by placing the torn sections face down on a sheet of Mylar. Then he ironed beeswax through the back. Over this he applied Belgian linen and more beeswax. Only unpurified, "dirty" beeswax satisfies Brewer. When an archaeologist friend gave him a nugget from an Egyptian tomb, the first thing he did was taste it. He was testing for sugar content and binding strength.

Brewer finished the Carter by petrolling off the beeswax and regouaching the cracks. He intends to document the process, which he compares to making a grilled-cheese sandwich, in a book on 10 case studies in restoration.

Every Dieruff piece was conserved except two. Brewer says the faces on Francis Quirk's oil-on-canvas could be removed from their white field, reassembled and remounted. Danko insists the price would be too high. Such a renovation, he adds, would violate the artist's goals.

Brewer delivered the last of three installments last summer. Danko booked the rededication of the collection for Dec. 19, 1991. The plan was wiped out by a flu epidemic.

Principal Michael P. Meilinger personalized the announcement by picking up Sardo, who had taught Meilinger everything from shared management of schools to rock formations to good living in New York City.

Two weeks later Sardo felt sick. The June morning began promisingly, with Sardo returning to

Dieruff to discuss his dedicatory plaque with Meilinger. The day went downhill when they learned that less than eight hours earlier an alumnus, thinking he was the skipper of "Star Trek," had ruined 17 of the 70 artworks.

Sardo cried and cursed at canvases yanked from frames, paintings dented by feet, watercolors ripped like confetti. To make matters worse, a school employee had tossed pieces of the collection into a dumpster.

"I seldom swear, except `damn' or `hell,' but I'm sure I said a few choice words that couldn't be taped," claims Sardo, who for three decades taught geography and geology at Dieruff and Muhlenberg College. " ... It was the antonym of exhilaration: it was debilitation." He remembers only one event more terrible, and that was the death of an 18-year-old son from a brain tumor.

Sardo feels better these days. After a year-plus restoration, and three lengthy postponements, the Dieruff collection was finally, officially, named for him on May 7. Now when he visits the school, he feels more like himself, more like the teacher who would see an artwork in the lobby, or the library, or the sculpture garden, and be challenged "to do my best to advance the cause of education."

Determining the price of mutilation caused the first delay, says Dennis Danko, caretaker of the Dieruff collection since 1986. According to the head of the school's art and music departments, appraisal to reimbursement took about a year.

Prior to damage the 17 pieces were valued at $15,100, notes Ron Engleman, business manager for the Allentown School District (Danko's guesstimate for the whole collection is $100,000). Damaged, the 17 pieces were worth $1,025. To restore the artworks, plus such items as a freedom shrine and photos of Dieruff principals, cost $9,492. Insurance paid for everything but the $1,000 deductible. The remainder came from the school district's general fund.

Delay No.2 involved restoring the restorer. James Brewer III, a conservator from Revere, Bucks County, worked for about two months, then underwent his second and third heart-bypass operations. He recuperated for approximately a year.

Brewer had many opportunities to act like a surgeon during his year and a half on the Dieruff items. Some were slashed. Others were deeply dented. Many carried the vandal's blood. The assignment was nothing new for Brewer, who has sealed the "X" of an ex-wife's razor blade, rubbed off linseed oil applied lovingly but wrongly every five years, and removed everything but an artist's blood.

Ask Brewer for a sample of his Dieruff work, and most likely he will mention Clarence Carter's "Study for Over and Above, #19." Artist and restorer have been partners for 15 to 20 years. One time, Brewer refurbished a Carter painting that had spent decades in a woodshed. This time, he had to bind six pieces of gouache on cardboard without damaging the watercolor.

Brewer began by placing the torn sections face down on a sheet of Mylar. Then he ironed beeswax through the back. Over this he applied Belgian linen and more beeswax. Only unpurified, "dirty" beeswax satisfies Brewer. When an archaeologist friend gave him a nugget from an Egyptian tomb, the first thing he did was taste it. He was testing for sugar content and binding strength.

Brewer finished the Carter by petrolling off the beeswax and regouaching the cracks. He intends to document the process, which he compares to making a grilled-cheese sandwich, in a book on 10 case studies in restoration.

Every Dieruff piece was conserved except two. Brewer says the faces on Francis Quirk's oil-on-canvas could be removed from their white field, reassembled and remounted. Danko insists the price would be too high. Such a renovation, he adds, would violate the artist's goals.

Brewer delivered the last of three installments last summer. Danko booked the rededication of the collection for Dec. 19, 1991. The plan was wiped out by a flu epidemic.

|

| Photo Portrait of President George Bush |

Danko rescheduled the ceremony for May 7. The idea, he notes, was to coincide with a spring concert and a reunion of school art angels. While the rededication was a month late for President Bush's visit to Dieruff, Sardo did get to discuss the collection with a federal education official.